The year after the clash with Ragnar Östberg, returning from Berlin, Dick Beer exposes at the Salon d’Automne in Paris, where he shall come back practically every year until his death in 1938. During ten years though (1922-1932), Beer is practically absent from the Swedish art scene. Starting in 1924 he is then permanently represented by galerie Carmine, rue de Seine. He rents a flat at Quai de la Tournelle, in a old town district that appeals to his interest for French history.

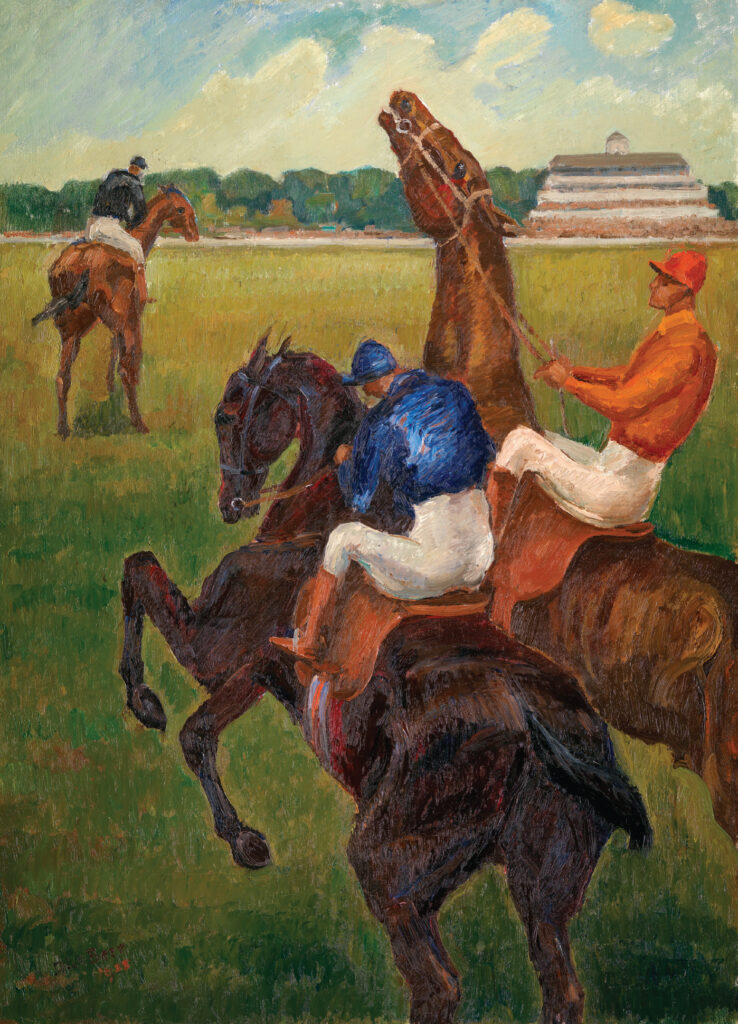

Three jockeys preparing, 1926

After 1928 he returns in the favour of most Swedish critics, rediscovered by an individual exhibition at galerie Carmine. In March 1932, Einar Rosenborg writes in the paper Social Demokraten:

“He presents no more canvases where the cubism appears naked in the daylight, so to say, but a frame of cubism remains in the landscapes such as in the view from Cagnes with the roofs climbing up the hillside bathing in the evening sun, or in the picture of the church in the same town; and also in the nude pieces which only three-four years ago had an almost brutal corporeality through the conferred volume sensation. When I talk about corporeality I would like to emphasise that Beer’s painting is not really sensual… He is a real painter and in several of the nudes with auburn hair and golden skin against a blue or green background the colour has become an element of nearly spiritual romantic lustre…”

The Italian press (Lidel of Milan, La Nuova Italia) also talks about him:

“I lavori del Beer, esposti oggi alla Galerie Carmine, rivelano una tecnica potente ed espressiva ed une visione d’arte assolutamente personale. I suoi paesaggi sono di une trasparenza e di una delicatezza squisita ; i suoi nudi sono impressionanti per la profunda osservazione e la rara potenza di colorazione.” (N.F.M. in La Nuova Italia, 3 November 1928).

And, more and more, the Parisian press:

”Parmi les bonnes toiles du Salon des Indépendants, il faut citer Chevaux de Course de Dick Beer (…) Dick Beer poursuit dans le recueillement et le calme le développement de ses remarquables dons artistiques. Son sens très averti de la ligne et de la couleur, sa vibrante sensibilité, sa maîtrise à exprimer le mouvement et la vie font de Dick Beer un des meilleurs peintres animaliers actuels.” (Raymond Sélig, Revue du Vrai et du Beau, 10 mai 1925).

And the magazine Comoedia in October the same year :

“Parmi les peintres scandinaves il faut signaler M. Dick Beer qui expose cette année au Salon d’Automne deux toiles importantes, Les Courses et Le Marché aux Chevaux (…) Le goût qu’il a pour les harmonies puissamment colorées, les tons lourds et riches où le bleu, le vert, l’ocre jouent leur rôle, il l’a mis au service d’une composition volontaire et réfléchie. Ses toiles sont solides, bien orchestrées et bien équilibrées. C’est ce qui fait leur valeur parce qu’on sent que tout cela n’est pas vain calcul et spéculation hasardeuse mais œuvre logique et consciencieuse qui laisse libre la personnalité du peintre.“

“Dick Beer est un homme du Nord qui regarde la France avec attendrissement. Sa pâte est claire, onctueuse ; il l’étend généreusement sur la toile. Ses paysages fluviaux nous ont paru légers, avec leurs justes reflets, leur humidité, le mouvement de leurs feuillages. L’oeuvre de Dick Beer est harmonieuse, savoureuse” (Paul Fierens, Journal des Débats, 12 novembre 1928).

“Le Nu à l’écharpe verte de Dick Beer, est un morceau très construit, très solide, et que la solidité des passages d’un plan à un autre embellit de la grâce la plus fraîche” (Thiébault-Sisson, Le Temps, 26 janvier 1930).

” M. Dick Beer, un Suédois, est doué d’imagination. Un Don Quichotte et son Sancho se promènent dans une jolie plaine, dont les vallonnements servent de socle aux fameux moulins à vent (…) Des nus de femme rousse traités avec une netteté robuste qui confine à la truculence, mais, en contraste, un petit nu, dans le demi-jour de l’atelier, attire par sa svelte et pure délicatesse” (the famous critic Gustave Kahn, Le Quotidien, 6 janvier 1931, announcing the exhibition at galerie Carmine in February 1931).

And in Daily Mail’s column by the Art Expert, February 19th 1930:

“It is particularly interesting to observe the effect produced on a Northern painter, accustomed to more or less misty atmosphere, by the southern landscapes. Mr Beer set up his easel in a very picturesque spot, the little village of Collioure. He has realised its wild and singular charm very well, as regards the structure of the ground and the shape of the trees, but he never deals with Midi scenery in the full glare of noonday sunshine, he seems to see it in a subdued form. His moonlight view of the village is particularly remarkable for the art with which he breaks up his colour tones. His Storm, showing boats scudding before the wind in Collioure harbour, is one of the most brilliant canvases and denotes his complete comprehension of nature in the South.”

In 1936 and 1937, two successful exhibitions are held in Sweden. Critics are no more a threat, on the contrary. He keeps now a studio on Bergsgatan in Stockholm. He has aged prematurely, “with the haggard looks of an ageing Beethoven or recalling even more precisely Rembrandt’s physiognomy with the clumsy nose, the sensual mouth, the piercing eyes”, according to the painter-journalist Kåge Liefwendal. He is tired but still has the travel demon inside. In the beginning of 1938 he visits his beloved Bretagne, it’s the wrong season. He goes on to Arles with the Mistral blowing in full. Back in Paris, Beer does not recover from a bad flue. In June that year, his only son passes Studenten, the consecration of Sweden’s secondary school. He takes the train from Gare du Nord, crosses Nazi Germany with the curtains drawn in protest. 25 hours later he is in Stockholm. He has to be admitted immediately to hospital with a pneumonia. Fatal in these days without access to penicillin.

In 1947 Kåge Liefwendal also notes :

“Many saw him as proficient, temperate and on the brink of being academic. But if we should judge him on these criteria it is important to remind that he had absolutely nothing to do with any academic elegance. On the contrary his way of painting lacks such pleasing appeal. His realism is harsh and has evacuated all that is related to flattery (…) In Paris’ studios at this time, Cézanne’s old maxim about painting cold and warm had been abandoned. Derain painted warm and warm, Othon Friesz and Kisling also. Yes, this was already the case with Matisse and the other masters in fashion. But Dick Beer went on struggling with cold and warm.”

(Continued)